Our Duty of Care is a group of healthcare professionals opposing the intentional killing of patients by assisted suicide or euthanasia

Our Duty of Care is a group of healthcare professionals opposing the intentional killing of patients by assisted suicide or euthanasia

Assisted suicide is prescribing a lethal dose of medication, at the request of a patient, for them to self-administer

Euthanasia is prescribing and administering a lethal dose of medication to a patient

We oppose euthanasia and assisted suicide because:

Vulnerable people must be protected from pressure to take their own lives

The lives of disabled & dying people have value and worth

Trust in the clinician-patient relationship must be preserved

Its the only way to prevent future extension to children, people with non-terminal illness and those who are tired of life.

Sign

up

to the "Our Duty of Care" campaign.

Stay informed about developments in the assisted suicide debate.

Tell

Colleagues

Discuss at unit meetings.

Organise talks.

Our team can help you.

Give

Financially

Support our campaign. We are funded and administered through the campaign organisation Care Not Killing.

Vulnerable patients will be put at risk by changing the law

The fear of being a burden may cause people who are vulnerable to feel pressurised to take their own lives. Page 12 of the Oregon Health Authority annual report from 2020 shows that 53% of people opting for assisted suicide mentioned the fear of being a burden on family, friends or caregivers as a factor in their decision.

The 2019 figure was 59%. This has increased from 25.4% in 2009.

Detecting abuse and criminality towards vulnerable patients will also become even harder than it is at present if doctors are licensed to legally administer lethal doses of medications. As many as 500,000 older people in the UK are vulnerable to abuse, as estimated by the charity Action on Elder Abuse. Over 450 patients had their lives prematurely ended by medical intervention at Gosport Memorial Hospital.

The lives of disabled and dying people have value and worth

Actively encouraging or assisting someone else to commit suicide is prohibited by law. The COVID pandemic has confirmed that, as a society, we recognise that life is inherently valuable. In our clinical experience, patients with frailty, terminal illness or cognitive impairment may have a low view of their own value and importance to others.

Clinical evidence suggests that patients with chronic and terminal illnesses are vulnerable to depression and suicidal ideation, yet with care and support can be helped to value the time that they may have left.

If we change the law to allow assisted suicide, we acquiesce with the view that some people don’t deserve full legal protection and their lives are of less value.

It's ethically wrong and it will harm the clinician-patient relationship

Assisting suicide has been prohibited by all international codes of medical ethics since the days of the Hippocratic tradition in Ancient Greece. It was forcefully repudiated by the World Medical Association Declaration in 2019.

Trust is the foundation of the clinician-patient relationship. The fact that a doctor or nurse might instigate death changes the relationship when a patient is ill and seeking care. There must be clarity that a doctor will never intentionally cause harm to patients.

The slippery slope is real...and dangerous

The only way to prevent incremental extension of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia is to not introduce it in the first place.

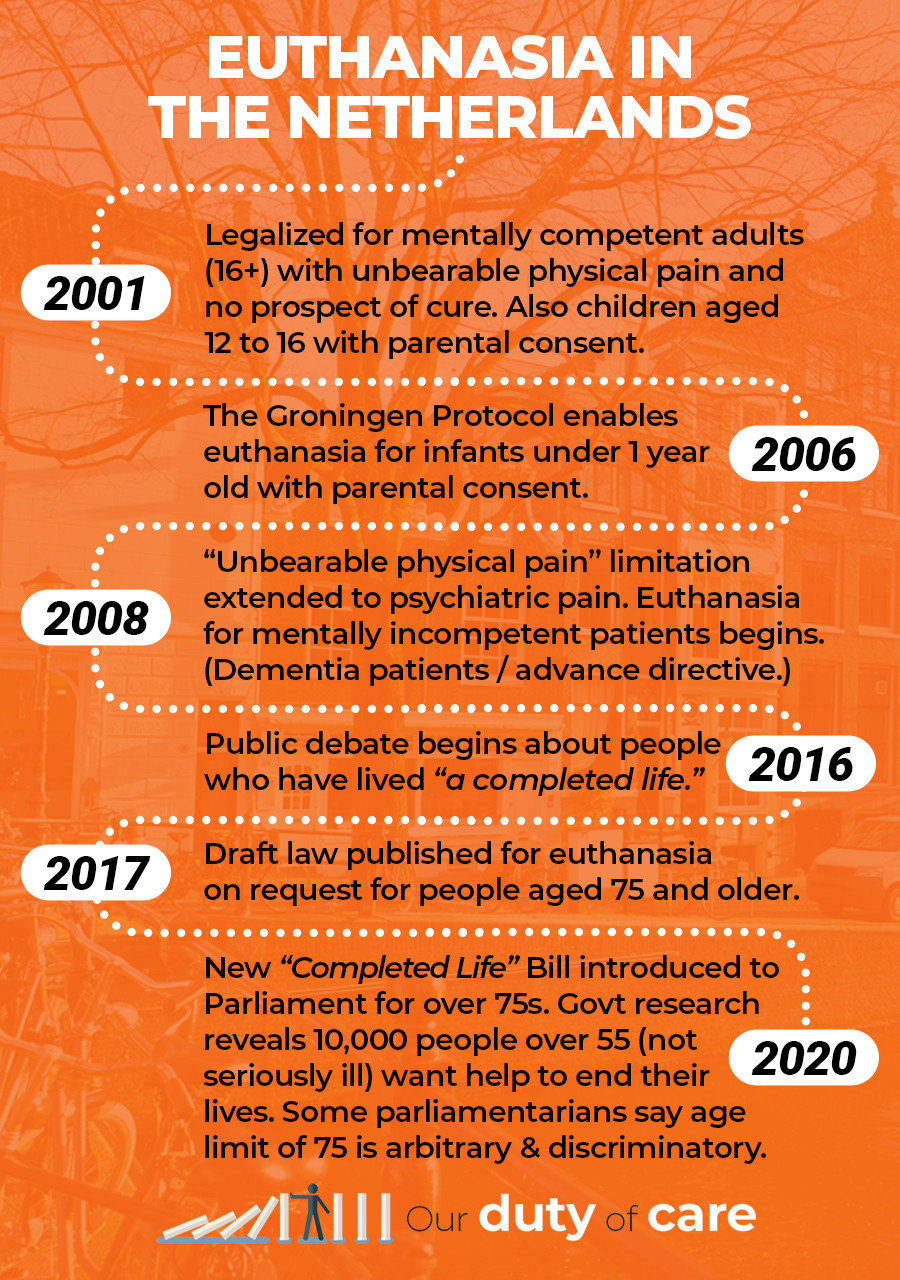

In other jurisdictions, the initial eligibility criteria have been progressively extended to include children and patients with psychiatric illnesses or dementia.

As soon as you accept the logic that some patients should have a healthcare right to choose this option, it immediately becomes discriminatory to deny that same right to other groups of patients. Principles of equality suggest that it should be available for all. One UK group is already arguing for euthanasia for patients with non-terminal disease.

Even if the original intentions are well intentioned, the fact that the categories of patients eligible for assisted suicide can be rapidly expanded means that the value we presently place on helping our patients to live fulfilled and comfortable lives, regardless of their illness or disability, will inevitably be undermined.

The terrible irony is that allowing euthanasia with the intention of enhancing patient autonomy would actually reduce the autonomy of those who are most vulnerable.

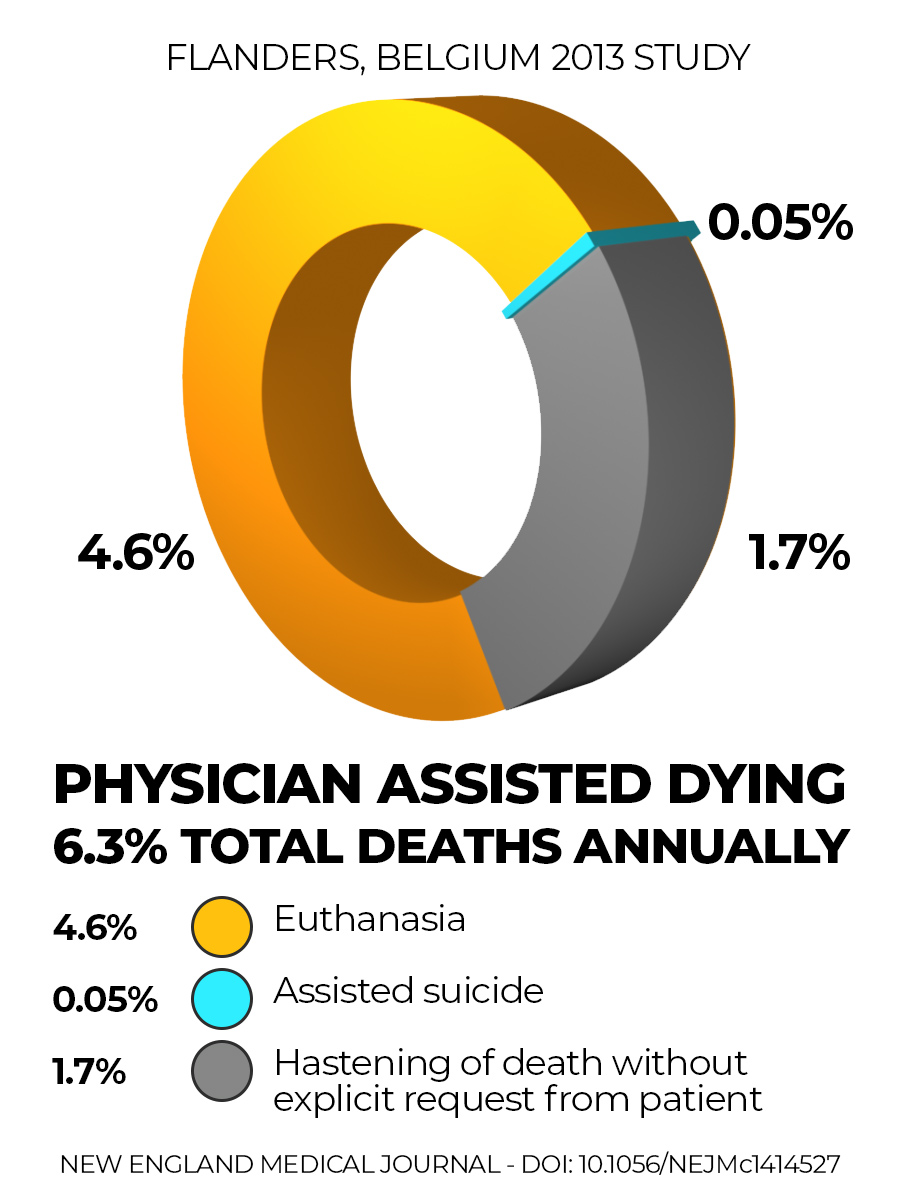

A review of involuntary euthanasia in Belgium by Raphael Cohen-Almagor was published in the Journal of Medical Ethics in 2015.

It found that 1 in 60 deaths in Flanders in 2013 were physician-assisted deaths which had occurred without the patient’s explicit request. 1.7% of all deaths.

This means that more than 25% of physician-assisted deaths were categorised as “Hastening of death without an explicit request from the patient.” This most commonly involved elderly patients over 80 years old, those in a coma and those with dementia.

If you don’t have institutional access, you can register for a free account with the NEJM and view these figures at

Recent Trends in Euthanasia and Other End-of-Life Practices in Belgium – Chambaere et al

Canada shows why neutrality is a myth

Canada legalised assisted suicide and euthanasia through its ‘Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID)’ legislation in 2016. The initial ‘safeguards’ have been eroded in just 5 years.

If the UK considers legalisation, Canada offers the most relevant international comparison because its society, political system, legislature and healthcare are so similar to ours.

"Few Canadian doctors foresaw that 'going neutral' would guarantee the arrival of euthanasia, or that promises of a shot in the arm for palliative care would be forgotten. Even fewer realised they would have no option but to cooperate with providing death on demand. It has become all too easy to end patients’ lives. Learn from our mistakes."

Dr Will Johnston Tweet

Family Physician and Professor

Vancouver, Canada

(BMJ 2019;364:l412)

ASSISTED SUICIDE -VS- PALLIATIVE CARE

We all share the same desire to reduce unnecessary suffering, so what is the right solution?

Assisted suicide campaigners claim to offer a cheap and simplistic solution to a complex problem.

Two Scottish academics have recently argued that assisted suicide and euthanasia could lead to significant financial savings, as money could be saved from ongoing healthcare costs and more organs may be available for transplantation. The obvious danger is that economic pressures to cut costs will determine clinical priorities and place pressure on doctors to help to end the lives of patients. And how do we quantify what the impacts might be if assisted suicide were to become regarded within wider society as an acceptable solution?

If assisted suicide were legal, it arguably becomes discriminatory to fail to offer euthanasia to those patients who meet other “safeguard” criteria, yet are unable to administer the lethal dose of medication themselves. Once the law is changed, the rest of the dominoes fall.

Healthcare professionals who wish to conscientiously object to being involved in the process will see their rights eroded over time. To understand how campaigners are seeking to introduce a systemic bias within NHS processes and protocols you just have to read their own stated intentions.

"The treatment can be pre-emptive. People should be encouraged to plan for their deaths. Every interaction with a clinician should prompt a review of people's end-of-life wishes. Of course, some people may not want to discuss this subject, and the consequences of that should be explained and ultimately respected, but not providing the option to plan ahead should be viewed as clinical negligence, in the same way that withholding pain relief would be!”

Sarah Wootton, Chief Executive, Dignity in Dying

When patients are cared for properly, they seldom want to end their lives

From our personal experience, we know that good quality palliative care is effective in relieving symptoms and helping people to live comfortable and dignified lives as death approaches.

Yet palliative medicine is chronically under-funded in the UK. Many hospices rely on charity funding. Limited research is directed at how services can be improved. Too many of our patients are dying without access to the care we know they need.

Palliative care is the right solution and it needs to be properly resourced

We uphold

-

to say no to burdensome treatment

-

to receive excellent symptom control

-

to change their mind about treatment choices

-

to access high quality social care and financial support to prevent them feeling a burden

We support

-

General Practice and community teams

-

Palliative Medicine

-

Integrated, multi-disciplinary medical care

-

Mental Health Services

GET INVOLVED

What can you do?

If you are a healthcare professional or medical student and would like to be kept up to date with the campaign and possibly get involved with future projects, please fill in the form below.

Tell colleagues

You can help your colleagues to be informed about the issue. Organise talks/debates/grand rounds and discuss the issue. Our team can help.

Get involved in your Association

If you are a member of the BMA, for example, how can you make your voice heard at the Annual Representative Meeting in 2021? Click here for more details about what's happening in the various Royal Colleges.

Give Financially

Donate to Care Not Killing to support the work of Our Duty of Care.